In the early days of the pandemic, the prospect of a deadly coronavirus surge at Laguna Honda nursing home in San Francisco seemed terrifying — and inevitable.

The public health department that ran Laguna Honda, the largest nursing home in the state, wasn’t equipped to handle a surge of cases at the facility. Residents felt scared. Workers, with little access to testing and protective gear, were frightened, too. City supervisors begged for help from the state and federal government to avoid a looming disaster. And Sen. Dianne Feinstein sent a letter to the nation’s secretary for Health and Human Services in March, saying help was critical to avoid a “catastrophic loss of life” at the home for more than 700 frail and mostly elderly people.

Concerns from public officials echoed those of advocates for the elderly who have criticized California’s nursing home industry as ill-equipped to deal with the virus.

Rodney Garrick (left) and Jennifer Carton-Wade walk down the hallway at Laguna Honda hospital in June.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)Now, four months into the pandemic, not one Laguna Honda resident or worker has died of COVID-19, public health officials say. Of the 721 people living there, 19 have become infected. And of more than 1,800 employees, 50 have tested positive.

Nursing home advocates say that with the right response and safety protocols, nursing homes can protect residents and workers from the coronavirus — Laguna Honda proves that. With help from the state and federal governments, San Francisco city leaders were able to create a response around the virus that prevented tragedy: creating COVID wards to keep people separate, training in proper infection controls for workers and enlisting a contact-tracing team to track how far the virus may have spread from person to person. Laguna Honda achieved what it did despite the fact that for several months, it couldn’t meet federal testing recommendations due to nationwide shortages.

“It’s amazing. Laguna Honda shows, yeah, you can do something. You can stop it,” said Patricia McGinnis, the director of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. “You can’t stop the infection completely, obviously, but you can prevent deaths. You can prevent it from spreading.”

San Francisco Mayor London Breed, who requested state and federal help for Laguna Honda in March, not only had a public duty to try and prevent disaster there, but a personal reason as well.

Josephine Ng waits to test a patient for the coronavirus at Laguna Honda hospital in June.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)“My grandmother was a resident at Laguna Honda for years before she passed away, so I know how important a place it is for our residents and families,” Breed told The Chronicle.

“We had to act swiftly to control the spread of the virus and ensure the health of residents and staff — especially as we saw what was happening at similar facilities across the country,” the mayor added. “While we’re still in the midst of this pandemic and must remain vigilant, we can recognize that the outbreak at Laguna Honda could have been tragic for residents, staff, and their families.”

What many people feared would happen at Laguna Honda has tragically come true elsewhere. Nursing homes and assisted-living facilities remain the main drivers of California’s COVID-19 fatalities, accounting for 46% of all deaths. The numbers are similar across the country. And although these elderly residents typically have health problems that make them more susceptible to the coronavirus and more likely to die from it, their vulnerability means they need a lot of extra protection from caretakers. Yet, the data show that doesn’t always happen.

Nurse Rosemary MacLeod (left) performs a coronavirus test on nurse Pauline Tran at Laguna Honda Hospital in June. The nurses are required to get tested every two weeks.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)Before Laguna Honda had its first COVID case, an outbreak that would become the nation’s deadliest was unfolding at another nursing home: The Life Care Center in Washington state, in early March. Employees in San Francisco watched in horror at reports that more than two-thirds of Life Care’s 114 residents and staff became infected with the coronavirus, and 37 people died.

Could it happen at Laguna Honda?

“We were worried,” said Troy Williams, an administrator at San Francisco General Hospital until the city’s health department created a “COVID command center” at Laguna Honda and put him in charge.

By the third week of March, three workers had contracted the virus.

Health officials knew more people would test positive and without a plan, the outbreak would be impossible to control. On March 27, Breed and Public Health Director Grant Colfax sent a formal request to the state and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, asking for help at Laguna Honda.

The next day, the state sent two infection control experts who stayed for a week. A day later, six nurses and epidemiologists arrived from the CDC.

They arrived at a place where many staff members felt helpless in the face of the unseen virus. Several had complained about being short-handed and lacking equipment. They said no one was listening.

But now the CDC team was there — to listen and help — for three weeks. Six workers had already tested positive. And by March 26, so had a resident.

With no isolation unit for infected residents, the CDC team helped the nursing home create a COVID unit around each sick patient’s room. That allowed up to 15 infected patients to be kept safely apart from other residents.

It’s not that Laguna Honda hadn’t quarantined patients before. But, as The Chronicle reported, social distancing rules and quarantine requirements were not always enforced before state and federal help arrived.

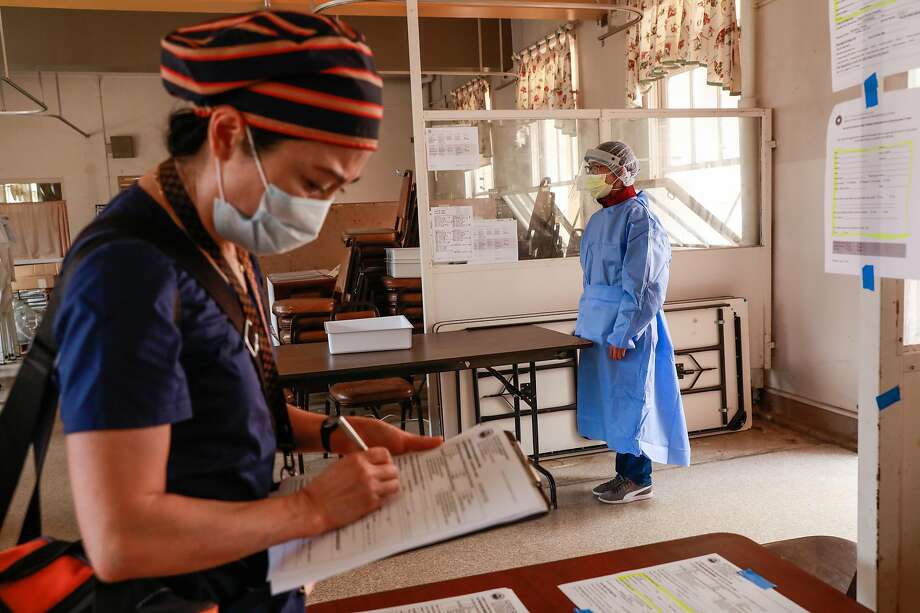

Jolie Wang (left) waits to get tested for the coronavirus by Josephine Ng at Laguna Honda hospital in June. Safety protocols at the hospital have helped avert the tragedy that has befallen other nursing care facilities suffering from coronavirus outbreaks.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)The nursing home began making a practice of transferring residents with the virus to the COVID unit for 28 days — two weeks longer than the usual quarantine time recommended by the CDC.

“The additional 14 days is to make sure that there are no additional cases that come up. It’s sort of a double quarantine,” said Irin Blanco, a nurse manager at Laguna Honda.

The CDC’s health team also taught nursing home workers — health aides and nurses — how to use personal protective equipment properly: sanitizing their hands before putting on gowns and wearing only gowns that fit. Infection-control staff also taught nurses when to wear a surgical mask and when it was necessary to upgrade to a more protective respirator mask.

Surgical masks and gloves were fine for just being near residents and other staff. But if anyone had to touch a resident — help them bathe, for example — then workers learned to switch to a respirator mask.

A coronavirus testing tent outside the hospital. Employees are screened for symptoms before entering the nursing home.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)Handwashing was also key, said Jennifer Yu, an infection-control nurse at Laguna Honda, who normally works to prevent flu outbreaks.

But not just any handwashing. Nurses and aides learned to use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer and rub it thoroughly over both hands. At the sink, they had to scrub their hands for 20 seconds, making sure they lathered the soap over each finger and knuckle, and washed under their nails.

“It’s not some magical machine, it’s really just washing your hands and using the right PPE,” Yu said, referring to personal protective equipment.

The CDC team also showed nurses and aides how to remove the protective gear to avoid contaminating hands, face and clothes.

Laguna Honda administrators now know that people going in and out of nursing homes, most often staff, are the main sources of coronavirus transmission.

Since March, every time employees enter the nursing home, they have had to sanitize their hands and take a new face mask. Someone checks their temperature and asks about symptoms that could signal COVID-19. Workers who pass receive a sticker to wear signaling their clearance.

Although the CDC team recommended that administrators test all 721 residents and 1,750 employees every two weeks, it wasn’t until May that the administrators had enough tests to achieve that. Testing shortages were reported nationwide.

Nurse Namuna Thapa is one of the employees who contracted the coronavirus at Laguna Honda Hospital and has since recovered. The nursing home’s protective measures, quarantine and testing protocols have helped limit the virus’ spread.

(Photos By Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)One employee who became infected was Namuna Thapa, a nurse who got the coronavirus from a coworker in early April. Thapa’s initial test was negative. But when she lost her sense of smell a few days later, a manager sent her home.

“Back then, a lot more was unknown,” Thapa said. “That kept me anxious.” She took her temperature three times a day and monitored her breathing. “I was ready to call my doctor if anything happened,” she said.

Michael, a 38-year-old resident with cancer who asked that his last name be withheld to protect his privacy, tested positive for the coronavirus on May 9. Michael said he didn’t know how he got sick. The Chronicle agreed not to publish his full name in accordance with its anonymous sources policy.

Nursing home staff immediately moved him to the facility’s COVID-19 unit, where he stayed in isolation for more than two weeks.

“In the beginning, there was some fear and just some anxiety,” he said. “But I had a very good support system. I am a spiritual person as well. When I made a mental resolve to turn isolation into solitude, and start focusing on the inner me, that’s what actually helped me to cope through that time of being isolated much better.”

Michael has recovered from the coronavirus but remains on lockdown with the rest of his unit at Laguna Honda hospital.

(Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle | San Francisco Chronicle)The staff at Laguna Honda also learned to do contact tracing from the CDC.

When anyone tested positive, health officials at Laguna Honda deployed a team of contact tracers to open an investigation and interview everyone who had come into contact with that person. The tracers warned those people to get tested for the coronavirus.

Managers sent exposed workers home to quarantine for at least 14 days. They have sent more than 35 employees home so far, or about 20 workers per patient.

The contact tracers interviewed Thapa while she was at home. Was she wearing a mask when she talked to others? Was she keeping at least 6 feet away from them? How long did their conversations last?

Because of sick workers, staffing shortages have become a challenge at Laguna Honda. So employees work overtime, said Blanco, who directs contact tracing and testing at the nursing home.

“We are saving lives by the things that we do every day,” said Williams, head of COVID incidents at the home. “The protocols that we put in place, we continue to use those every day. We have a really excellent set play when we have positive cases.”

In June, San Francisco public health officials began offering those protocols to other nursing homes in the city.

“I’m hopeful that what we learned as a community at Laguna Honda can be applied elsewhere to protect some of the most vulnerable to COVID-19,” said Colfax, the city’s public health director. “We are going to be living with this virus for awhile.”

Sarah Ravani is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: sravani@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SarRavani

The Link LonkJuly 27, 2020 at 06:03PM

https://ift.tt/2WVTTRC

A deadly coronavirus outbreak seemed inevitable at SF's Laguna Honda nursing home — but that's not what happened - San Francisco Chronicle

https://ift.tt/38hkzRl

Honda

No comments:

Post a Comment