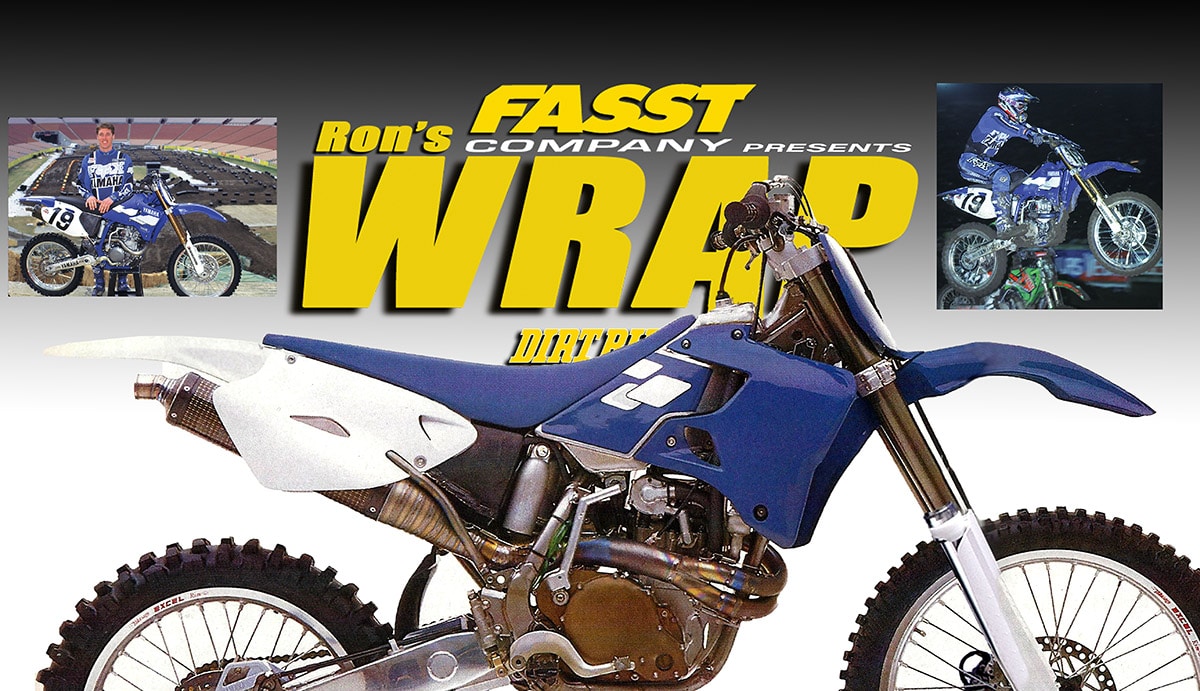

Back in the late ’90s, motocross looked and sounded very different. Then, in late 1996, Yamaha made an announcement that changed everything. That was when the news came out that Yamaha would be using its one-time exemption to the production rule in order to develop a new four-stroke motocross bike in the course of the 1997 racing season. The first look that the world got of the YZM race bike was on the cover of the February, 1997 issue of Dirt Bike. Here are three stories that appeared over the next few years in DB that together tell the story of the coming of the four-stroke era. First, let’s look at that story from February 1997 when the YZM was first revealed.

The bike you see in front of you is the future of motocross. In ’97 Yamaha has announced that it will campaign a four-stroke in the U.S. National MX series. The AMA has made a special exception to the production rule so that Yamaha can develop what the company fully believes will become the motocross bike of the future.

Why? That’s easy to figure. Unless you time-warped from the ’40s, you know that the two-stroke engine is living on borrowed time. There are factions in government that insist the two-stroke as we know it today must go away, that it is too dirty and too ecologically unfriendly. In Los Angeles, there are laws in effect that prohibit the sale and use of two-stroke leaf blowers and lawnmowers–and California is already seeing the first steps in regulating two-stroke off-road bikes. At this point, competition bikes are unaffected by the new regs, but you don’t have to be a brain surgeon to figure out that environmental regulations aren’t getting any looser. In the next few years they will only get more and more strict, eventually affecting motocross.

Yamaha figures we have had all the warning we need. That’s why the YZM400F was built. Doug Henry will race it for the first time in the Gainesville 250 National (AMA rules already allow four-strokes a displacement advantage in the 250 class, although so far only Husaberg has taken advantage of it). Europe will also have a racing program. Technically, this will be a development year for the YZM, so that a production bike will be ready in ’98 or ’99, but Keith McCarty wants to do more than just use the AMA National motocross series as an excuse to make some test laps. He wants to win. At the least, he wants to make a podium by the season’s end. McCarty is Yamaha’s race team manager, and the development of the bike has been tossed completely into his lap. That’s very unusual. The racing department concerns itself with winning races, while developmental duties are more typically tossed to the R&D department. However, as McCarty puts it, “We are designing this bike from the ground up as a motocrosser, not a trail bike.” What better way to develop it?

The bike itself is very cobby right now. Nothing about it has truly been finalized. For the moment, it is a liquid-cooled, double-overhead-earn 400 in a frame that mimics YZ250 geometry. The engine’s centercases are CNC-machined out of billet. Basically, the machinists started with an enormous block of aluminum and cut away everything that didn’t look like a four-stroke engine. It has a four-speed gearbox, but even that can change. The most striking thing about the motor is its width, or lack thereof. It’s actually about an inch narrower than the YZ250 motor. It is a wet sump motor, too, meaning that the oil is carried in the cases rather than in a separate tank. Usually wet sump engines run very hot, but the YZM has disproportionately large radiators to compensate.

More details: the carb is a Keihin CR of undisclosed venturi size. This is a roadrace carb with the slide rolling up and down on roller bearings for less throttle effort. The ignition is programmable so that the team can change ignition curves between motos if they need to. The pipe is a two-into-one design with a carbon fiber muffler. Carbon fiber bits can be seen all over the bike in places such as the intake boot between airbox and carbo Also-of course-all the nuts and bolts are made of titanium. This is a true works bike, the likes of which has not been seen in this country since ’85. Right now we would estimate the weight of the bike at under 240 pounds, but there is much more weight that can be shaved. In later models, the centercases will probably be sand-cast, and that is worth a few pounds right there. As for the frame, the engineers figured that a YZ was a good place to start.

So right now the bike uses the same angles and weight bias as a YZ, but that will undoubtedly change as the season progresses. The factory has promised that it will do whatever the race team requests as quickly as possible.

“I know what the factory can do,” says McCarty. “Back in the early ’80s we went through a slump. Bob Hannah had just come came back after a broken leg, and he didn’t like the race bike that Broc Glover and Mike Bell had been developing. So Japan sent over a team of engineers and said they couldn’t go home until Bob won a race. We ended up lowering the engine and making all kinds of changes, and Bob finally won the Saddleback National. Then those guys went home.”

Do they really expect to win? “No, not right away,” says McCarty. “Doug has only ridden the bike once, right before Thanksgiving. It was a two-day test session in Japan. Right now we don’t even know if it’s suitable for supercross. That decision will come later. The plan is that Doug will ride it in the outdoor races and then ride a YZ in supercross, but that could change. The bike is making over 50 horsepower, so it’s fast enough, but we don’t know if it makes the right type of power yet.”

Even if the bike doesn’t win this year, it’s certain that Yamaha will get a lot of attention with the YZM. It won’t be hard to notice Henry. He will be the only one on a four-stroke, the only one on a works bike and the only one on a ’99 model. It will be an interesting year.

ROGER’S TAKE

The controversy started almost immediately. At the time, Roger DeCoster was still on staff at Dirt Bike, a position he held since 1994. He was also Suzuki ‘s Race Team Manager by then. That gave him a vested interest in the matter–at the time, Suzuki had no plans for a four-stroke motocross bike, although the DR-Z project was then underway. In the May, 1998 issue he wrote the following column, expressing his displeasure with the displacement advantage that Yamaha had.

Should four-strokes be given a displacement advantage for racing? It depends on your idea of what racing is all about. In my mind, racing is all about letting the best man win. Rules that promote this are good rules. Rules that don’t are bad. Motocross has actually managed to stay pretty pure in that respect over the years. At first, a racer could use anything he wanted as long as it was under 500cc; it didn’t matter if it had one cylinder or six, or if it weighed 50 pounds or 500. In those days, everyone used four-stroke singles because they made the most suitable power and were the most reliable. In the search for more power, some riders started adapting road-racing engines to MX–engines from the AJS 7R, the Matchless G50. Some even used Norton Manx road-race powerplants. Later there was a period when Triumph Twins were popular, mostly in the Famous Rickman Metisse chassis.

In the meantime, a 250cc class was born. It didn’t have the interest or the prestige of the 500 class, but it did provide the opportunity for some different engine designs to come into play–most notably the two-strokes. At first, two-strokes were the joke of the paddock. They sounded funny, they were terribly temperamental and unreliable. If a two-stroke rider stalled his bike in a race, you would see him lap after lap with his fuel-flooded bike on its side and the gas petcock closed, trying to get it cleaned out. A cloud of blue smoke would hang over the whole scene. It was a comically common sight. In those days, promoters loved to throw stream crossings into the course, and usually the main line would be clogged with drowned-out two-strokes.

Yet, with all those shortcomings, special rules were never used to give two-strokes any kind of advantage. They were never given extra displacement. They were never given a head start. The four-stroke riders didn’t have to wear blindfolds or start backward. Two-strokes became competitive on their own. First two-strokes took over the 250 class, and eventually made an impact on the 500 class. Jeff Smith was the last four-stroke rider of that era to win before the two-strokes dominated.

The age of the big two-stroke started with Paul Friedrich in ’66 and lasted almost 30 years, until Jacky Martens won the championship on a four-stroke in Husqvarna ’93. That brings us to ’98, with Doug Henry making his presence known on the American racing scene with the YZ400F thumper.

This time around, however, it isn’t engineers who are making the change occur; it is the rule makers. The AMA and FIM amended the rules allowing four-strokes to have more displacement than two-strokes in every class. There are lots of reasons to support this: crowds love the sound of four-strokes; new emissions regulations are forth-coming; four-strokes are the engine of the future, so we might as well get ready, and so on. These are all based on good intentions, but doesn’t the AMA have enough things to worry about without taking on the burden of meeting the new emission standards? Isn’t that the problem of the manufacturers? If that’s a legitimate reason, then why aren’t these oversized four-strokes required to actually pass the emission standards before entering a race?

Trying to level the playing field is a good goal, but how do you decide what is truly level? There’s no scientific formula for comparing two-strokes to four-strokes. The AMA lets 550cc four-strokes race against 250cc two-strokes, and 250cc thumpers race 125s. The FIM puts 360cc four-strokes in the 250 class. There’s no way to come up with a universal formula because the bike that gets the most development will always be the most competitive. Right now, two-strokes are on top because they received all the development in the ’70s and ’80s. Then European manufacturers like Husqvarna, Husaberg and KTM saw an opportunity to stimulate four-stroke sales with racing success.

That opportunity came about mostly because the 500 class had become less competitive as the Japanese companies slowly pulled out. Still, the attention that these manufacturers received must have stimulated Yamaha. If tiny Husaberg got so much interest from its thumper program, then think of the success that a massive company like Yamaha could earn. Yamaha certainly did a great job, both on the works bike on which Henry won the Las Vegas Supercross and the production version.

Too bad we couldn’t see into the future in ’96 when the AMA approved the displacement spread. At that time, no one took four-strokes seriously. No one thought that four-stroke development would be carried out by anyone other than a few tiny companies with microscopic R&D budgets. Even Yamaha’s race team officials probably didn’t know what was going on in Japan. All that changed after Las Vegas, though. It isn’t that Doug Henry has a big advantage over the rest of the field–quite the opposite. It seems he has to push harder and take more chances than any of the other top riders. But he clearly has more power–isn’t that why they invented classes to start with? Now that the rule has passed, it’s hard to go back. During the last meeting, Yamaha raised a legitimate point: After the company has spent thousands of dollars on the project, it wouldn’t be fair to change the rules. Kawasaki’s Bruce Stjernstrom thinks that displacement rules should be absolute, that 250cc two-strokes should race against 250cc four-strokes. Team Honda’s position is that four-strokes should be segregated into another class. Neither solution seems likely for now.

I can’t help but wonder what would happen if some top executive at Honda got really mad and decided to go all-out just to prove a point. Certainly, Honda has the resources to finance a project that no one else could match. There are not enough MX bikes sold to justify a project like that on an economic basis, but Honda has been known to launch such operations on corporate pride. Maybe it’s already happening with 250 four-strokes aimed at the 125 class.

For now, I think a compromise is in order. The AMA and the FIM need to agree on a displacement gap. Perhaps putting the four-stroke cap at 360cc, as the FIM does now, would be unfair to Yamaha. But we should at least move the AMA limit down to 400cc.

More than anything else, though, we need to be ready to change-and keep from painting ourselves into a corner–again.

THE REAL WORLD SHOOTOUT, 1998

In 1998 we decided to see for ourselves whether or not four-strokes and their displacement advantage were more effective at the production level. We could have compared the new Yamaha YZ400F to a Yamaha YZ250 two-stroke of the same year, but as it turned out, the YZ250 wasn’t especially good that year. The Kawasaki KX250 was the easy winner of the 250 motocross shootout in 1998. The YZ400F and the KX250 were compared against the stopwatch in the March, 1998 issue. Here’s what we said:

When Yamaha embarked on the YZ400F journey, the engineers aimed it directly at the ’98 YZ250, and didn’t stop until the thumper would smoke the 250cc two-stroke in every category, The idea was to build the first motocross four-stroke capable of beating everyone on the gate-not just other thumpers. During preproduction testing, the YZF was consistently faster than the YZ250, to the (claimed) tune of three seconds per lap. This pleased the Yamaha guys to no end.

However, in our January shootout, the ’98 YZ250 finished midpack. It was down some 2.5 horsepower to the KX250, and the Kawasaki also outshined the YZ in low-end torque, pull on overrev, fork action and stability. When the roost settled, the KX250 had soundly beaten the YZ on every track in the comparison. Yamaha was smart to compare the YZ400F to a two-stroke 250 motocrosser, but time prevented Yamaha from comparing it to the best 250cc MXer of ’98–the Kawasaki KX250. While Yamaha was developing the YZF, Kawasaki was finalizing the ’98 KX, so it would have taken a time machine for Yamaha to obtain the new KX to test against the YZF Nothing is stopping us from answering the burning question now, though. Can the YZF beat the top 250cc motocross bike of ’98? Welcome to the duel to decide the Bike of the Year!

On the dyno, the KX and YZF were virtually tied in peak power, with each cranking out 45 ponies. However, the KX dropped like the Titanic once it hit 9000 rpm, and the YZF revved out to 11,000! On the track, it played out like this: at the end of every straight, when the KX rider was grabbing that next gear, the YZF motored past like the KX was tied to tree. The YZF’s usable spread of power was about double that of the KX, and it showed on any straightaway.

Coming off turns, though, the KX250 snapped to attention and revved quicker than the YZF, because it made comparable low-end torque and twice the number of power strokes for any section of track. If there was traction, the KX would put a bike length or two on the YZF. However, if there wasn’t a rut, berm or ample loam to hold the KX’s rear tire straight, it slewed sideways while the YZF was hooking up and hauling.

In deep sand, the KX’s snap got it on top and plaining quicker, while the YZF tended to struggle and wander a bit before getting up to speed. On slick clay mud, the YZF ruled, because the KX wasn’t anywhere near as tractable.

Trittler reported that he could clear a short-approach, sit-down double on the YZF, but the KX couldn’t because of wheelspin. Every test rider thought the KX would be faster overall but came away impressed with the YZF’s potent, usable engine. The YZF isn’t just fast for a thumper, it’s fast!

Yes, the YZF is 18 pounds heavier than the KX. Yes, the KX has a steeper steering-head angle than the YZF (wheelbases were equal). No, the KX is not the king of corners! We found that the YZF carried much more cornering speed than the KX, regardless of the tightness, roughness and slickness of the turn. In high-speed, whooped-out sweepers, the YZF would hold its line, while the KX would invariably drift wide. Flat corners were no contest–the YZF would stick like glue, while the KX would be fighting to find traction. The F even required less input when slamming berms.

About the only time the KX would have an advantage was in deep sand. The YZF would push its front tire on flat, sandy turns, and it would take longer to accelerate out of tight turns.

Our YZ250 picked up some head-shake this year, so we were worried that the YZF might make like a wet dog, too, but it didn’t. What it did do was track straighter over every section of track than the KX. Not only was it more stable, it was more stable while going faster than the KX. Think about that. The YZF lets you go faster, longer than the KX, because you are not fighting to make the bike go where you want. The only time the KX took less effort was when the YZF’s front tire would wander, as it did in sand and on some flat turns. Steering harder into the turn would bring the front end back in line, with little input required. We soon adapted, though. The worst downside to this was that the YZF wore out front tires faster than the KX. Considering that the KX wore out rear knobbies much faster than the YZF, we decided we could live with that.

Cliff and dune jumping aside, it takes a stopwatch to tell if a bike (or setting) is faster than another. At Glen Helen, Ron was more consistent on the YZF, and his times were a half-second faster on the YZF. Don was a 1.5 seconds faster on the Yamaha, and he could turn more laps on the thumper before tiring. At our high-desert suspension test track, Spud was almost a full second faster on the YZF, and he made less mistakes on it. Damon could also turn faster laps longer on the Yamaha. At Castaic, Shane could turn faster laps in heavy traffic on the Yamaha than he could when he had the track to himself on the KX. When people heard that booming thumper, they got the heck out of the way! The psych factor was much higher with the thumper. Damon again turned his best laps on the YZF, and he could do twice the laps at speed on the Yamaha over the Kawasaki, even though the track was rougher when he rode the F!

There you have it. From intermediate to pro, every rider was faster on the YZ400F than the KX250. It proved easier to ride, faster, more nimble through turns, and more stable at speed than the best 250 of the year. It made better power over a wider spread, and it carried its weight well. Best of all, it turned anti-thumper folks into thumper freaks. Bivens would get all misty-eyed when we pulled him off of the YZF, and Trittler ordered one the next day. The Yamaha YZ400F is definitely the Bike of the Year, maybe the decade. In one fell swoop, Yamaha has raised motocross to a new level, and it did it with four-strokes and five valves. We can’t wait to see what ’99 will bring!

See you next week!

–Ron Lawson

The Link LonkFebruary 20, 2021 at 12:53PM

https://ift.tt/3dvXejm

WHEN YAMAHA & THE YZM CHANGED EVERYTHING: THE WRAP - Dirt Bike Magazine

https://ift.tt/2ZqQevw

Yamaha

No comments:

Post a Comment